Home -

Foreword -

Georg Philipp -

Piano Business -

Lymington -

Trees -

Related Topics

Alphabetical Links

|

In Honour of a Beloved Husband

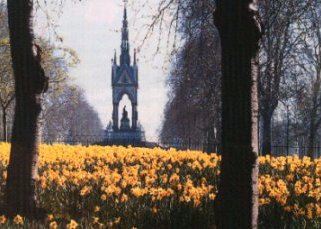

The Albert Memorial is one of the great sculptural achievements of the Victorian era, and for sheer scale, opulence and complexity is hard to match. The architect was George Gilbert Scott, and he was much inspired by miniature medieval shrines, and also by the medieval Eleanor Crosses, set up by King Edward I in memory of his dead Queen, Eleanor, wherever the funeral procession went. (Though the original cross in London did not survive, the current Charing Cross is closely based on the earlier design, and suitably shrine-like.)

The Memorial composition has a large statue of Albert seated in a vast Gothic shrine, and includes a frieze with 169 carved figures, angels and virtues higher up, and separate groups representing the Continents, Industrial Arts and Sciences. The pillars supporting the canopy are of red granite from the Ross of Mull, and from a grey granite from Castle Wellan Quarries, Northern Ireland. These latter pillars, of which there are four, are from single stones, weighing about 17 tons each. Each pillar took eight men about 20 weeks to finish and polish. The Albert Memorial was noted at the time of its completion as being one of the most costly works in granite of the period. Darley Dale stone was used for the capitals, and the arches are of Portland stone. Pink granite from Correnac, Aberdeen, appears with marble in the pedestal on which the statue of Albert sits.

The sculptor in overall charge of designing the statuary of the memorial was H. H. Armstead, and he made the Sciences, and together with J. Birnie Philip, made the 169-figure Frieze of Parnassus. J. B. Philip also designed the angels, and the eight Virtues were sculpted by J. F. Redfern. Mosaics were by Salviati of Murano, to designs of John Clayton of Clayton and Bell. The most impressive groups are the four Continents and the four Industries, entrusted by Armstead to eight eminent sculptors.

Putting the gleam back in Albert's eye

An interview with Alasdair Glass the man in charge of the repairs and re-guilding of The Albert Memorial.

"In case you have ever wondered how to gild, here's the secret. First you get your "size", which is a sticky liquid made of linseed oil and other things, and slap it on. Then you wait 24 hours until it is tacky, and next you take your gold leaf, which comes in books of 20 sheets, atoms thick, three inches square, separated by waxed paper. You rub the brush against your hair or cheek to pick up static, then you brush it gently on and repeat; and for reasons I cannot explain the gold sticks, immortal, imperishable and unchangeable save for its natural mellowing to the deep buttery tones, already achieved by the angels 200ft above against the blue autumn sky."

There they are, four angels renouncing worldly honour and four with arms raised, wafting to heaven the spirit of Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, carried off by typhoid at the age of 42, leaving an inconsolable queen, and a people feeling faintly guilty that they had been so suspicious about the energetic German Prince Consort.

This month, October 1998, for the first time since 1914, when the Government took Albert's double layer of gold away - allegedly because he acted as a beacon to raiding zeppelins, but in reality because the gleaming statue was attracting anti-German feeling - Albert will shine forth again.

Amid fireworks and a Son et Lumiere show, Her Majesty the Queen will reveal her great-great grandfather, 12.2 tonnes of melted bronze cannon, wearing his garter robes in a posture which Sir George Gilbert Scott, designer of the memorial, called "dynamic repose", and coated once again in 23-and-a-half carat gold.

For eight miserable years the Memorial was in its weird thermos-like tent, a constant reproach to Britain's conception of itself as a top nation. Though to be fair to our own age, the mistakes were made in the construction, from 1864-70. From the outset, rain penetrated the roof causing the iron to rust and pushing out the decorative cladding and staining the sculptures green. Ten years ago, passers-by were being peppered by pieces of Salviati's superb mosaics, pinging off from on high. A great clod of lead cornicing was found on the steps. "It was uncontainable, every time you sent a steeplejack up he did more harm with his boots than good with his hands," said Mr Glass.

For eight miserable years the Memorial was in its weird thermos-like tent, a constant reproach to Britain's conception of itself as a top nation. Though to be fair to our own age, the mistakes were made in the construction, from 1864-70. From the outset, rain penetrated the roof causing the iron to rust and pushing out the decorative cladding and staining the sculptures green. Ten years ago, passers-by were being peppered by pieces of Salviati's superb mosaics, pinging off from on high. A great clod of lead cornicing was found on the steps. "It was uncontainable, every time you sent a steeplejack up he did more harm with his boots than good with his hands," said Mr Glass.

It was not until 1994, with £8 million from the Government and £2 million from English Heritage, that work began. A grand mobilisation was necessitated of half-forgotten arts. Mosaic boffins from Italy, lead workers from Shropshire, ironworkers from Norwich, experts in bronze, copper, stone, marble, enamel and new techniques for deterring pigeons: these were among the 150 artisans involved. They removed and replaced more than 100 tons of lead, and installed new syphonic drainpipes.

This great portentious jewel is magnificent in its political incorrectness. Even if you could find sculptors today capable of working the Campanella marble, to produce the 213ft of the Parnassus frieze, imagine the outcry if you asserted the supreme importance of 169 dead white males, almost all of them European: Homer, Dante, Corneille, Milton and Erwin von Steinbach.

The group representing "Africa" shows a native leaning on his bow, harkening to a female European figure. "Asia" shows a beautiful semi-nude woman on top of an elephant unveiling herself, symbolising the moment of European discovery.Comments from Mr Glass:

"I sit at the back of the bus and wait for the gasps of pleasure from the tourists. The Japanese love it because they have this great reverence for their ancestors ... It's not kitsch. I think its totally self confident and it defies criticism."

( Part edited from The Daily Telegraph 1998)

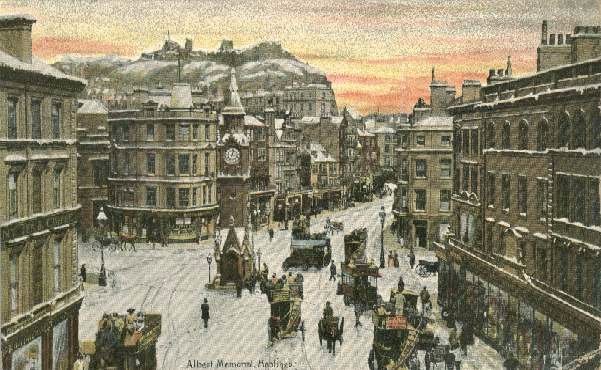

A friend has since sent me this picture of bygone years, showing a small edition of the Albert Memorial standing in the centre of Hastings in Sussex. I understand a fire destroyed some of it and the rest was removed and not replaced again.

back to top - The Albert Memorial