Home -

Foreword -

Georg Philipp -

Piano Business -

Lymington -

Trees -

Related Topics

Alphabetical Links -

Email: family@klitzandsons.co.uk

|

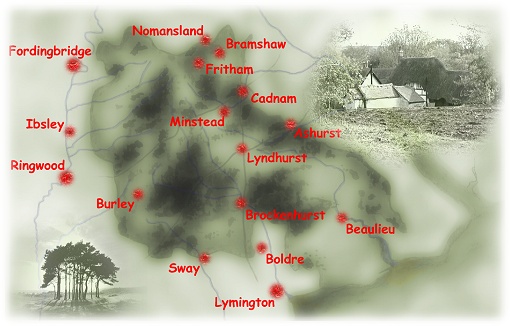

"TALES OF THE NEW FOREST"

by PHILIP KLITZ

First published in 1850

LATEST NEWS

NEWS

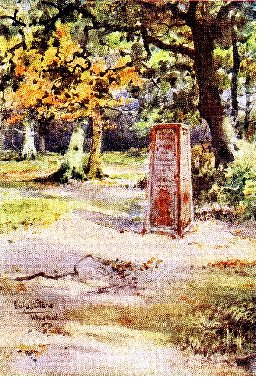

"Tales of the New Forest" was written and printed in 1850 and only one or two elderly copies remain. Bill Klitz wanted to reprint the book and collected some items towards this, but no progress was made at that time. Bob wished to try again for a reprint and with use of Ann's computer new copies are now available. Some punctuation has been altered to make it easier to read but Bob has selected appropriate pictures which have been added to enhance the plain text. You can read some text samples on this page

Copies of the book can be obtained from the Lymington Museum.

Telephone: 01590 676969 - Email the Museum

or send an enquiry email from the Logo at the top of every page.

You can now read the whole book Tales of The New Forest in pdf format

TO MRS. SOUTHEY

MADAM,

When you acceded to my request that I might be allowed in this manner to associate your Name with these humble pages, many pleasurable feelings were engendered by your kindness.

Treating, as these stories chiefly do, of Forest Life it was to me most gratifying to be permitted to inscribe them to a Forest Resident of so great literary fame. True I might have been daunted in thus daring, as it were, your critical opinion, before which I could not safely present these artless and unstudied papers, but I was too conscious from many past kindnesses, that the structure of these stories would not be severely scanned and I knew that if your literary acumen were of the highest order, your disposition to judge kindly is likewise uniform and unbounded.

Gratitude moreover, for long and unvaried patronage, not only in the course of my own professional career, but in a portion of my father's, prompts me to embrace this occasion to assure you of the lively remembrance with which your former favours also are cherished by,

MADAM,

Your faithful and obliged Servant,

PHILIP KLITZ.

Southampton,

February, 1850.

READ MORE ABOUT MRS SOUTHEY

TO THE READER

In travelling out of line of composition, the Author of the following Sketches would briefly explain to the Reader (whose indulgence he entreats), the casual circumstances from which they have their origin.

In the course of a summer-days ramble in the Forest, in the company of an esteemed friend, the writer related to his companion the substance of some of these stories, with the incidents of which he had become familiar by lengthened residence in a Forest town and by professional visits throughout the entire district.

His auditor suggested that the tales that had been told him might furnish themes for more lasting record by the pen; and, thus encouraged, he diverted that instrument from its wonted practice among crotchets and quavers and turned it to "literary" uses.

Most of the stories that follow, appeared in the columns of the 'Hampshire Advertiser' and the idea of their re-issue, in a collected form, first occured to certain friends for whose judgement in matters less personal he has great regard. He trusts that in adopting their advice on this occasion, he will not be charged with presumption, seeing that his little Book - although it be the first-born - is not thrust forward as a child "of parts", but modestly, as needing favour and as having no pretensions.

LIFE IN THE NEW FOREST

A great diversity of chararacter is observable in the Forest, which in large towns it would be impossible to recognise - the habits and pursuits of many, nay hundreds, who may properly be termed "Foresters", are so very distinct from the generality of what may be called Citizens, as to form a most striking and singular contrast.

The life of men engaged in a distinct line of business, such as merchants, tradesmen, mechanics, artisans and labourers is one of routine, relieved only by the occasional holiday, or by temporary depression of business. These we may see in most large towns, especially in the manufacturing districts and the difference between them cannot be so distinctly perceived. The regular process and unvaried habits of the factory fill up a most monotonous existence; the smoky atmosphere of the foundry, the glowing furnace, the noisy accompaniments of the steam engine, the incessant whirl of machinery, at once convince the beholder that powerful must be such influences upon the moral and physical character of those who are thus employed. Certainly custom is a great familiariser. These men and boys - the whole of them - have been accustomed to such influences, as were their parents before them. Their education, if they had any, has not exceeded the requirements for their expected spheres of labour. Thus they live on day after day, in a round of noise and bustle, contented as long as they can secure the means of sustaining themselves and their families.

The toil of the week is relieved by the hope of enjoyment on Saturday evening and the rest of Sunday. With some, where education has been effectual, the sober, quiet and industrious enjoy the comfort of domestic peace and the solace of divine worship; while with others, it is to be lamented, dissipation and misery abound from a variety of causes.

Contrast, however, the life of "the lean and smutch'd artisan" with the life of the forester, and what a change is visible! From the rising of the sun to it's going down his hours, for the most part, pass under "the open firmament of heaven" or the leafy canopy of the forest woods. But here, as with the mechanic, the effects of education are clearly perceptible.

Here may be found the daring deer-stealer, fleet of foot, cunning in strategy, who, from the contiguity of the coast, was wont to couple with the poacher's craft the hazard of a smuggler's life. Here, likewise may be found the frugal and domestic cottager.

Then, what a variety is there in the forester's avocations! At the prompting of the season or the sky, he is "everything by turns and nothing long" - excepting, indeed, when certain years of humbler industry have rewarded him with the dignity of a pig proprietor. Through turf-cutting, bark-peeling, carting (in all its branches), potato-growing and sundry other employments, the thrifty forester attains his 'ne plus ultra' in a herd of swine, which he is priviledged to turn into the forest at certain times of the year.

Where, as in his case, a quiet, sober and industrious exercise of the manual powers procures a livelihood for a numerous family. His mode of life, though active, if it assumes a sameness of character, differs essentially from the sombre uniformity of the mechanic.

Where, as in his case, a quiet, sober and industrious exercise of the manual powers procures a livelihood for a numerous family. His mode of life, though active, if it assumes a sameness of character, differs essentially from the sombre uniformity of the mechanic.

The cultivation of the earth by judicious hands is an important feature in the great allotment of labour for mankind; but in the noble forest, where nature dwells in her greatest and grandest power, the efforts of labour are of a toilsome but much more simple character. Here as she throws off the fruits of the seasons, from the early birth of spring, each succeeeding change produces some variety beneficial and congenial to man; and it is in his occupation of watching the revolving time, the attitude of his uplifting hand receiving from the passing season it's peculiar gifts, that the character of the forester becomes interesting in its native simplicity and patient depending upon Providence.

Here, if he has implanted in him any sympathy with that feeling which ought to pervade every breast, he finds ample space for admiration - abundant incitements for gratitude to the Great Power who so wonderfully worketh all things to promote his creatures' happiness.

Surely an ingenious heart, thus moved, may compassionate without pride his fellow man, doomed to the suffocating confines of the factory, whose toil bears with it no refreshing evidence - as does the forester's so constantly - that Heaven is man's generous helper whenever he will stretch forth his arm and labour worthily.

Following chapters:

New Forest Laws and the New Forest Scenery

Richard and Mary

The Life Insurance

Joe Gates

Peculiarities of Forest dialect - The Ven'zon Mark, or The Lost Child

THE DOCTOR

If I become, as it shall seem, "really too" enthusiastic in my admiration of the personage I am about to describe, I do humbly trust to be excused. Let the considerate reader review his "list of friends" and confess, that as it respects one, or two, or three in that company, he could never tire of talking and feel a pleasure too in recounting their virtues. Even so is it with my humble self at this present.

The little doctor's very name strikes the electric chord of memory and I am carried back to the sunny fields of Childhood and of Youth and revel in their glad associations. Happily for us it is impossible to resist these influences, which, at seasons few and far between, burst upon the care-worn spirit in it's grave and anxious thought, like gleams of sunshine through the sombre clouds.

Expressions of praise in this good and kind little doctor have already appeared in these pages. He stands before me now, just as he was wont to do when those inevitable maladies the whooping cough, the measles and other family ailings, brought him to our house. As we mustered just a dozen, there were in "catching" complaints generally three or four down at a time!

Ah! He was something like a doctor! Were we not delighted when he visited us? Though to be sure we knew his visit would be followed by more "doctor's stuff". But then we loved him, and love, which is said to make all things "beautiful", at any rate made the doctor's physic palatable.

Not a child was there in the whole parish but enjoyed his company - not an adult with whom the doctor was not an especial favourite so that it may be supposed his practice was extensive. Still, he never became rich - he was too good, too charitable, albeit from the range and the respectability of his connection his professional revenue must have been large.

Not a child was there in the whole parish but enjoyed his company - not an adult with whom the doctor was not an especial favourite so that it may be supposed his practice was extensive. Still, he never became rich - he was too good, too charitable, albeit from the range and the respectability of his connection his professional revenue must have been large.

But then consider his habitual benevolence and the extent of his pension-list! Medicine, soup and wine, tea, coffeee and sugar - these were all dispensed as they were most required; moreover he would indulge the worn out veteran of sea or land with the means of whiffing his cares away, and supplied the old Scotch soldier's widow with the frequent consolation "o' a wee pinch". I am thus minute, because many who were more scrupulous in their gifts, were wont sometimes to cavil at these last-mentioned benefactions of the doctor; but he defended himself by observing, that while he certainly would discountenance offensive habits in the young, in the aged, use had so long confirmed them, that when combined with poverty their prohibition was severely felt.

But it was in the exercise of his profession that his real worth was most conspicuous. How did he give up rest, recreation, everything desirable to his own comfort for the benefit of the sick and suffering! Early and late, night and day was he in request, never complaining of the self-sacrifice exacted by duty and never better pleased than when his cast-down patient was looking up again.

Then, and at other times, when a sly joke would be "in season", what happiness was his to let off little humorous quips at which no patient could resist a smile. "Ha Ha! Mrs Muggins", he would remark to that well-known monthly, "Are you here"? - Then I'll warrant there's mischief brewing!" Then by pleasantry or pathos, as the case stood in need of rallying or sympathy, would he turn to the "expecting" matron and leave her more satisfied than ever that there wasn't such another doctor in the world as the subject of our story.

During some of his visits, where he found it necessary to divert his patient's attention, he would relate some romantic adventure or tale of danger to which he had been exposed.

More following chapters:

The Doctor's Story

Our Club Day

Peter Batt

THE WOUNDED STAG

| 1 | 2 | ||

| It was a lonely winter's eve; The moon's pale beaming light Shone brightly forth, so soft, so clear, So calmly through the atmosphere, That all on earth, both far and near, Look'd pure and silv'ry bright! |

The twinkling stars came peeping out, And willing seemed to try Who'd shine the brightest, fairest, best, The while all earth lay hush'ed in rest, Yet, ever and anon, to test. A cloud came sailing by. |

||

| 3 | 4 | ||

| The bracing coolness of the air, So crisp, so pearly grey, Play'd o'er the surface of the brook, Which, ever as a leap it took, Would gently stop, as if to look At what had checked it's way. |

The forest trees of leaves bereft, Stood forth in outline bold, Their branches tipp'd, as oft of yore, In glitt'ring rims of frosted hoar; The furze in folds was mantled o'er By snow so chill and cold. |

||

| 5 | 6 | ||

| That gentle slope which summer time Had deck'd with bright green fern, Was cover'd o'er by bitter frost, And all it's lovely freshness lost, As to and fro, in storms was tost, By winter, cold and stern. |

'Twas such a night in Rhinefield Walk; The keeper was at rest, When all at once he thought he heard A sound - it was not voice, or word - Perchance the plaint of some lone bird, By lawless fowler prest. |

||

| 7 | 8 | ||

| But see! Who lurks in yonder glen, And noisless steals along? I fear thou art bent on aught but good; Too well thy calling's understood; Nay, leave the stag to range the wood, He will not want it long. |

Thou wilt not surely kill and steal, And break the laws of God; Nay, leave him to the cold, cold bed, Wheron he rests his branching head; O, do not send him with the dead, By artifice and fraud. |

||

| 9 | 10 | ||

| He'll best thee, man, if face to face, Unarm'd, thou wilt appear; Let nature's weapons prove the truth - Thou could'st not, though thou'rt yet a youth, Withstand the onslaught, fierce, uncouth, Of a brave forest deer. |

Shame, shame! On man, who thus betrays Both cruelty and fear; Who skulks behind a hedge to kill, By dint of art or cunning skill, A creature form'd by God's own will, A coward is, that's clear. |

||

| 11 | 12 | ||

| I glory in the lawful sport That's given to man in chase; But in that sport give space and breadth - A single chance of life or death - And not at once deprive of breath, But win by strength or pace. |

Why e'en the bird which high on wing Hangs floating in the air, The sportsman true would scorn to take, Whether in field, by bush or brake, On marsh or mount, or on the lake, Unless the game is fair. |

||

| 13 | 14 | ||

| Hark! Hark! Now, through the brittle air The echo of that gun, Around it flies - now back again, But not a sound will e'er remain To drown the moan of dying pain So treacherously won. |

But all thy skill, thou poaching elf, Will bring no gain to thee; For see! What's this comes limping near, Moaning loud with pain and fear? By heav'n, 'tis the wounded deer - Now from the foe he's free! |

||

| 15 | 16 | ||

| And wither would'st thou wend thy way, Thou injured harmless thing? Ah! To the keeper's lodge - I see; For he has e'er been kind to thee: When roaming in the forest free, Thy fodder he would bring. |

Last night he fed thee at the gate That leads down to the farm, The while thou lick'd his hand with glee, And he in turn caressing thee: He little thought this sight to see, His favorite come to harm. |

||

| 17 | 18 | ||

| And thou would'st call him from his rest, By buttng at the door; He hears thee now - quick from his bed He lifts his weary, dreaming head; But now all sleep has from him fled, And he has grief in store. |

Here, wife and Mary! Edward, George! Come, see the wounded deer; Some poaching rogue has shot poor Jack, And see, he's broke the poor thing's back - Ned, go and find a stout warm sack, And quickly bring it here. |

||

| 19 | 20 | ||

| Fetch cloths, we'll staunch the bleeding wound, There's life left in him still! Ah! Good kind keeper it is in vain, For nought but death can ease the pain, A few short minutes yet remains, And he's beyond thy skill. |

The children all with tearful eye, The keeper and his wife, Crowd round the dying stag, whose eye Expressive rests on those close by, Who vainly hope, yet kindly try To save the poor thing's life. |

||

| 21 | 22 | ||

| And see, now from his dying face The trickling tear-drops fall; The poor dumb creature cannot tell Who wounded him or why he fell But seems to speak a last farewell, To keeper wife and all. |

Look! Keeper, look! Once more to raise His drooping head he tried; One ling'ring look, that seem'd to say "Kind master, can't you let me stay? O, why should I be sent away?" And then the poor stag died. |

|

Further chapters:

MOOTY 'OODGATE |

back to top

Tales of the New Forest